lip lit: a name of one’s own

In 1967, literary critic Roland Barthes wrote in his seminal essay The Death of the Author that

writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing.

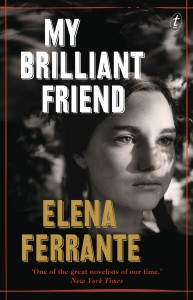

In 2015, in a rare interview with The Paris Review, Italian author Elena Ferrante wrote of her motivations for adopting a pseudonym:

I came to feel hostility toward the media, which doesn’t pay attention to books themselves and values a work according to the author’s reputation. It’s surprising, for example, how the most widely admired Italian writers and poets are also known as scholars or are employed in high-level editorial jobs or in other prestigious fields. It’s as if literature were not capable of demonstrating its seriousness simply through texts, but required “external” credentials. […] it’s not the book that counts, but the aura of its author.

Both authors muse on what benefit the reading of a novel is given when biographical details about the writer are added to the mix; both come to the conclusion that a work of art should be able to do the talking for itself. Details of an author’s birthplace, creative habits, political opinions, favourite colour and so on are all irrelevant to the reading, enjoyment, and understanding of the story.

On 3 October, 2016, however, the New York Review of Books took one more stab in a long line of guesses as to Ferrante’s “true identity” by publishing the suspicions of an Italian journalist, Claudio Gatti. Gatti dug through some financial records, inferred a few things from other published academic works, and came to the conclusion that Ferrante was an Italian translator named Anita Raja.

Raja has denied that she is the author of the best-selling Neapolitan Quartet; but then, so has every other suspect. The validity of Gatti’s theory is neither here nor there: the real question is, why do we – the public, the media – think we are entitled to know who the ‘real’ Elena Ferrante is – and why do we think it matters?

Most of the speculation about Ferrante’s pseudonym, prior to the exploitative New York Review of Books article, talks about the author’s choices in terms that can only be described as uncomfortable. Her decision to remain anonymous is billed as tantalising and teasing, and the underlying assumption is that Ferrante’s choice has only ignited the public’s curiosity more, and that it is just what she wants. It’s a stunt, or a ploy: she wants us to ask. As though Ferrante is doing the book-tour equivalent of starting a story and then quickly saying, ‘Oh no, I can’t tell you that.’ The media have been quick to assume that Ferrante’s plea for anonymity – to let her work speak for itself, to be left out of the media machine – is really a manoeuvre designed to get more attention – despite the fact that her novels are clearly well-written enough for such a cheap tactic not to be necessary. Who could possibly not want to be famous? they ask. There’s a sinister undertone to Gatti and co.’s actions, and it’s this: hey, sweetheart, who asked you what you want? A fake name, a short skirt: we’re all just begging for attention.

Attempts to discover Ferrante’s true identity are attempts to reveal what has deliberately been hidden. It is a stripping away – of Ferrante’s privacy, and of her agency. Perhaps the media don’t respect Ferrante’s request for privacy because they fundamentally see famous people – particularly women – as public property.

And if we did know who Elena Ferrante ‘really’ was – ignoring the spuriousness of notions like reality and truth when it comes to something as subjective as a novel – what benefit would it give the reader? If we could match real people to characters, make pilgrimages to the author’s childhood home, would we really be making an honest attempt to understand the novel better? Or would we simply be engaging in another act of erasure: taking an exquisite work of fiction and reducing it to thinly veiled biography. Ferrante couldn’t possibly be this good, she’s just writing down what happens to her and adding a bunch of he-said-she-saids. It’s an effort designed to undermine the creative work in its own right, to render it and its author humbled, stripped down, destroyed. Just a girl, nothing more.

It may seem simple, on the surface: your curiosity may have been aroused, as mine was, when you heard that Elena Ferrante was a pseudonym. You may have wondered how she managed to keep her identity a secret since she began publishing under the name in the 1990s. But if you take a second look; if you listen to what an ordinary thing it is that Ferrante is asking for; it might not seem so simple after all. It might begin to look like just another way that the world doesn’t respect what women want, when they say they want it. It might look like just another dismissal of the word no when it’s coming out of a woman’s mouth.