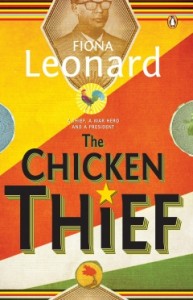

lip lit: the chicken thief

Close your eyes. Go on. Do it.

Now what can you see?

Nothing? Really?

Look again.

Can you see the computer in front of you? Yes – you can feel it there with your fingertips. Can you see your cup of coffee steaming beside your elbow? Of course – you can smell its bitter aroma melting in your nostrils.

And thus we meet Alois, a highly successful chicken thief who has ‘always seen much better with his eyes closed’.

Fiona Leonard’s novel The Chicken Thief is a fast-paced story, with action expertly punctuated by insightful and sensuous descriptions of Africa and its landscape, both political and natural. We feel the ‘malicious wind’ that throws dirt in the faces of passers-by and we hear the silence of chickens about to be hypnotised and shoved in a sack.

Elsewhere described as a melange between a Dan Brown thriller and an Alexander McCall Smith mystery, The Chicken Thief recounts the story of Alois, a young man who uses hypnosis to steal chickens for a living after he quits a well-paying but dishonest job at the Ministry of Finance, where he worked for a government and a President with their own dirty secrets.

Caught in the act one evening, Alois is enlisted to locate and steal something bigger and more significant than merely chickens. He unintentionally lands himself the somewhat problematic task of rescuing and protecting a war hero, presumed dead twenty-five years beforehand.

What is surprising about this war hero, Gabriel (yes, named after the Archangel) is that she is, in fact, a woman. The story oscillates effectively between Alois’ story, Gabriel’s and that of the President, a man whose name we never learn.

The President’s name is not the only information Leonard deliberately withholds. The country in which the story takes place is also an indeterminate location somewhere in Southern Africa.

Leonard has been asked in numerous interviews to reveal the country in which she envisages the book being set but each time, she has politely declined the opportunity to divulge this information, though has confessed to having a particular location in mind when writing the book.

Leonard has travelled through and lived in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Namibia, South Africa, Botswana and Malawi, and currently lives in Ghana. Her reasons for withholding the book’s location, she explained in an interview for The African Book Review, were largely centred around her desire to ensure no prejudice or preconceived ideas could be used in forming readers’ perception of the country’s struggles for independence and the character of the President.

As a reader, at first there is a niggling, like an itch needing to be scratched, of wanting to place the events and people in a particular location or a certain period of history. But then it becomes clear that there are larger messages at stake in this novel. And this choice to withhold detail also serves as a reminder to us that this work is, in fact, fiction.

Leonard’s decision to make her war hero a female also provides an interesting dimension to the characters of her novel. Alois is clearly the main protagonist; it is his voice we follow across every page, except for certain chapters where the President is allowed to speak and think. We never really hear Gabriel’s voice. Instead, we relive her story through Alois’ eyes and ears.

The country’s political unrest simmers just below the surface and develops into a strong undercurrent for the whole novel and becomes Gabriel’s fighting cause.

“You don’t become President because it’s a good idea. You become President because …no one kills you before you turn up for work,” is Gabriel’s thought-provoking explanation for refusing the Presidency. While this may seem dramatic, we are nonetheless forced to consider the fight for independence in many areas of the world today and the effects of the instability and corruption often associated with it.

In the novel, this corruption culminates in a (perhaps overly) theatrical scene in Parliament House where Gabriel talks publically and passionately of her pain and imprisonment. This is perhaps the only criticism of this delightful book; because it moves at such a pace, the reader is kept at a slight distance and is not awarded the chance to really feel Gabriel’s sense of loss. Though perhaps this was always the plan, as it is really Alois’ story and the story of a country, albeit unidentified.

The writing itself is poetic, which effectively contributes to Alois’ characterisation and identifies the voice of the story as his own. Leonard’s beautiful phrases, poignant descriptions and references to African proverbs provide insightful glimpses into humanity and make you smile in spite of yourself.

And so, while reading with our eyes closed may be a challenge on a logistical level, this book certainly requires all our senses to be engaged in order to fully appreciate its subtle beauty.