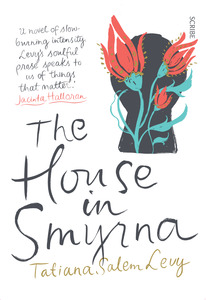

lip lit: the house in smyrna

According to Martin Amis, that sharp satirist and white male English literary giant, there are two things that literature can’t do. The first is sex. Amis agrees with his father, Kingsley (that bigoted white male English literary giant), who believed that sex has the effect of de-universalising the reading experience. Good sex, Amis junior opines, is out of the question.

Fiascos are acceptable for their comic value, as are novels in which everything revolves around sex—for example, he cites the brilliant Lolita. The second is dreams. ‘Tell a dream, lose a reader,’ Henry James said. Tatiana Salem Levy’s debut novel, The House in Smyrna, tries to do both, with unexpected results.

Translated from its original Portuguese (Levy is Brazilian), The House in Smyrna is narrated by a suffering female who in alternating sections dialogues with her dead mother, addresses an abusive partner, and narrates her grandfather’s immigration from Turkey to Brazil, her parents’ temporary exile in Portugal, and her own journey to back to these countries.

The switching between situations—each kept short, with spare prose—creates a dreamlike effect: the novel reads like a sequence of snippets of letters, memories, and indeed, dreams. The narrator has nightmares about being locked in her grandfather’s house in Smyrna, which in ‘real life’ she sets out to Turkey to find. In others sections, she says:

‘I tell (make up) this story about my ancestors, this story of immigration and its losses, this story about the key to the house in Smyrna, about my hope of returning to the place that my forebears came from,’

Levy implies that the writing process is a vehicle for her to resolve the pain caused by her mother’s death and her partner’s abuse. The narrator—as unreliable ones tend to do—blurs the lines between reality and fiction, and we don’t know whether her trip to Turkey is ‘real’ or written. As a result, the woman’s dreams are contiguous, rather than in conflict with the novel’s reality. Levy tells a dream and the reader reads on.

With respect to sex, Amis may have a point. There is plenty of sex in The House in Smyrna, much of it cringe-worthy. Often, the loftiness of the prose verges on comical in its incongruity: ‘I remained standing while you implored something between my legs, in a language understood only by the two of you, my clitoris and your mouth’. ‘Your penis was hard, upright, and I liked seeing it like that, as if it were looking at me too.’ There are also overcooked similes about vulnerability: ‘It was as if you were touching my organs directly, my blood, my flesh, without any protection.’ These scenes are, as Kingsley put it, de-universalising, because they create a rift between writer and reader by causing one to doubt whether people really think such abstract things when having sex, or as Levy puts more loftily, ‘making love’.

Sex, however, is important to the novel insofar as it relates to central ideas about the body. The narrator’s body is both an object of desire and a vessel through which she fulfils her own longings. On the first date with her partner, she recalls: ‘I listened to every word and felt my body quake: with fear, desire, happiness.’

Eventually, when their relationship sours, sex becomes the means by which the body is degraded, which removes agency and causes the paralysis the narrator professes to suffer from in the book’s opening paragraph: ‘I wouldn’t know what to do with this body that has been unable to move ever since it came into the world.’ The scenes in which the sexual assault is described are raw, confronting and genuinely tragic. They are disturbing reminders of the horrors of domestic violence. On top of her, her partner ‘delighted in my pain, and asked: Isn’t it good?’

Pain and physical suffering are acutely felt by the narrator, partly as an aftereffect of abuse, partly as a result of her mother’s death, and partly due to the weight of the past that she feels burdening her. Decay of the body is frequently alluded to: the narrator tends to her dying mother, ‘covered with sores, riddled with holes, filled with pus, with its acidic smell, its smell of death’. In another section, her own body is ‘Dilacerated, covered in open wounds, purple and yellow spots, boils.’ Death, she says to her mother, ‘had been lying in wait for us the whole time’. And of course, saying goodbye is a major theme of the book.

But beyond death, beyond the moving meditation about losing those who are dear to you, the novel is about what it is to love and to live.