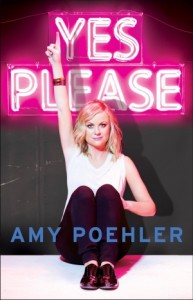

lip lit: yes please

Amy Poehler’s newly-released Yes Please is part memoir, part self-help book, part opportunity to peer into the Poehler family scrapbook. Dotted with photos, youthful creative writing attempts, and full-colour scans of personal mementoes ranging from college playbills to handwritten acrostic odes to Tina Fey, Yes Please is a bright and cheerful tour through Poehler’s life so far. The book covers everything, from her childhood through to her Saturday Night Live days right up to present-day reflections on the penultimate season of hit comedy Parks and Recreation.

Amy Poehler’s newly-released Yes Please is part memoir, part self-help book, part opportunity to peer into the Poehler family scrapbook. Dotted with photos, youthful creative writing attempts, and full-colour scans of personal mementoes ranging from college playbills to handwritten acrostic odes to Tina Fey, Yes Please is a bright and cheerful tour through Poehler’s life so far. The book covers everything, from her childhood through to her Saturday Night Live days right up to present-day reflections on the penultimate season of hit comedy Parks and Recreation.

Poehler describes her book as a ‘missive from the middle … a street-level view of my life so far.’ As she wryly puts it, ‘Yes Please is an attempt to present an open scrapbook that includes a sense of what I am thinking and feeling right now. But mostly, let’s call this book what it really is: an obvious money grab to support my notorious online shopping addiction.’

Poehler is a funny and endearing narrator who strives to keep her audience entertained throughout the book. The essays are deliberately arranged in a non-chronological fashion, jumping from stories centred around her early days with the Boston College improv group that got her into comedy in the first place, to her mother’s account of the day she was born to an almost stream-of-consciousness name-dropping session in the essay ‘Humping Justin Timberlake’.

Poehler occasionally attempts to use Yes Please to impart her wisdom: these moments are, sadly, examples of the weakest writing in the collection. The advice might be sound, but the delivery is not: she descends into self-help book cliches that are so generic that they end up meaning nothing.

When she writes just to tell the story, however, there is an honesty in her self-reflection that is rewarding. In her essay ‘Sorry, Sorry, Sorry,’ Poehler tells the story of a 2008 SNL skit that she was part of that was criticised for being offensive to people with disabilities; Poehler was not just criticised in the media, but was contacted privately by a couple who work as advocates for disabled children, who informed her that the person she had made a joke about in the skit was actually a real person struggling with cerebral palsy. In the essay, she gives background to the sketch and how it was written, and talks about how the fast-paced nature of a show like Saturday Night Live means occasionally she is unaware or uninvolved in the creation of the skits. Then she writes: ‘See how I am trying to distract you from the shitty thing I did?’ Poehler is brutal with herself: she makes her excuses and then tears them down for the reader to see.

The essay ‘I’m So Proud of You’ is the chapter that resonated with me the most. It details Poehler’s experiences as a woman working in a male-dominated industry: ‘Once a woman turns forty,’ Poehler writes, ‘she has to start dealing with two things: younger men telling her they are proud of her and older men letting her know they would have sex with her.’ She talks about the techniques she uses to stand her ground, confronting people in her line of work who seek to undermine her or dismiss her, and the exhaustion that comes from having to prove yourself over and over again to these men.

The last few years has seen the publication of many memoirs of famous, fabulous women, from Tina Fey’s Bossypants to Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl. These memoirs have been sparkling, amusing, intelligent books, but there’s also something strange: they’re also ever-so-slightly embarrassed to be there. Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl probably exudes this hangdog air defensively: visit any comment section of any article written about Dunham since she scored her impressive book deal, and you’ll find one if not many obnoxious commenters smugly noting that ‘This’—whatever objection they have to her this week—’is why twenty-year-olds shouldn’t write memoirs.’ Poehler’s Yes Please is no exception: there is a distinctly apologetic (somewhat tinged with the argumentative) tone to Poehler’s writing, weighed down as it is with qualifications – she’s only forty, she’s not claiming to know everything, she’s just writing about her own experiences. Amy Poehler as Your Humble Narrator, who has no business writing a memoir or giving advice—or so she implies.

There’s a weird undercurrent here: we don’t think women are worth listening to, as a society, and subsequently these women feel bad about having something to say. Thankfully, Poehler chose to say it anyway, and I am immensely glad that she did, but it still bothers me that these women have had to fight their inner demons to get to say something as simple as: I am a human, I have experiences, thoughts, feelings, I am going to put them down on paper and try to figure out what it means to be alive. These women are billed as self-indulgent and self-obsessed for daring to express some self-reflection. Their treatment is unequal, their fears un-shared by their male counterparts. It might seem small, their lives might seem ordinary or insignificant in the face of grander-scale world crises, but I am still of the opinion that these perspectives and experiences matter.

Yes Please is written, as most memoirs are, for an audience already familiar with Poehler’s work and already in love with her. The strong, wise-cracking woman shines through on every page. Yes Please gives an insight into Poehler’s life and character without gossiping or confessing: you won’t find intimate details of her friendship with Tina Fey or a play-by-play guide to the breakdown of Poehler’s marriage. What you will find is an amusing, charming glimpse at the woman who has been making you laugh for years.