#writingwhilefemale

Every now and then, a Twitter hashtag gets real. It exposes injustice. It strips back a culture to bare experience. On the feminist scene we’ve heard stories from thousands of women through #everydaysexism and #yesallwomen – the newest hashtag to make waves is #writingwhilefemale.

It’s the brainchild of Foreign Soil author, Maxine Beneba Clarke.

‘Despite the plethora of incredible female writing talent in Australia,’ she says, ‘There are still more men on the shelf and in the pages of regular publications then women.

‘I started #writingwhilefemale as a way to catalogue the trials and tribulations of being a female identifying writer in Australia in a manner that’s public, inclusive and collective. Twitter seemed like a fast and accessible way in which we could vent our frustrations or discuss our experiences, and potential solutions to some of the problems we face – whether we were at home drafting a poem with the kids around our ankles, or on lunch break from a staff newspaper job.’

The hashtag began on 11 December, with Aussie writers like Lee Kofman, Jo Case, and Jessie Cole contributing to the dialogue.

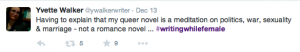

In all industries, women are treated differently to men. #writingwhilefemale is a collection of the implicit sexism within books, poems and publishing: the greatest themes are women writers not being taken seriously (often pigeon-holed into chick-lit and ignored by as a literary piece), underrepresentation, and lack of confidence.

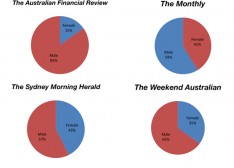

‘We need to have this conversation because as a general rule books written by Australian men are more likely to be read,’ says Clarke. ‘The illuminating yearly Stella Count, conducted by The Stella Prize, also shows us that newspapers review far more work by men than by women. Women are still underrepresented in almost every category of literature.

‘Alongside fabulous initiatives such as the Australian Women’s Writing Challenge and The Stella Prize, we need to start talking about the grassroots day to day struggle, and supporting women all the way up the chain.’

Laura Jean McKay, author of the short story collection Holiday in Cambodia, has watched the Twitter feed evolve since its conception. What’s stood out to her are that ‘books written by women are often received, marketed and bought differently,’ she says. ‘Also, the writing itself might be produced under different circumstances to man writers. And pitching, publishing and marketing needs to change to make way for the brilliant writing that is being produced, and not celebrated enough in the wider literary world.’

McKay knows the book industry’s marketing is gendered. If female authors don’t directly tackle ‘male’ issues, novels are often squashed into the chick-lit genre and dismissed. She pushed against this when Holiday in Cambodia was published.

‘I was very aware, when my book was being published, that I didn’t want a book cover design that female writers are often pushed towards. I made that clear to my publisher, who in turn came back with a decidedly non-gendered one.’

The feed took on a positive turn, too, as female writers discussed the brilliant things about the industry.

Melbourne-based writer and editor Jennifer Down was also impacted by #writingwhilefemale, particularly by observing the experience of mums who juggle kids and career.

‘I don’t have children, but I was hyper-conscious of all the tweets from women who balance motherhood with writing. Writing is so poorly paid, and sometimes—for me at least—hard to justify as a creative pursuit, which compounds things further.

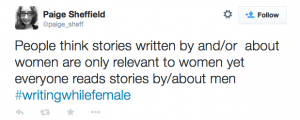

‘Paige Sheffield’s tweet struck me because it almost goes without saying. There’s an interview with Junot Diaz where he talks about how women tend to write men very well, but often men struggle to write female characters. I’m sure that’s to do with what we’re used to reading, and the representations we’re accustomed to seeing.’

In Down’s experience, male writers dominate the scene.

‘Masculine voices simply seem to be accorded more weight much of the time. I used to do music journalism, which was an incredibly blokey field. The voice of the publication was lads-having-a-laugh, and other articles they published would occasionally use words I considered slurs, but I never wanted to say anything in case I were thought of as a crazy social justice warrior or touchy feminist. I like to think I’d have the confidence to speak up now.

‘I also remember listening to the young men in the first short fiction class I ever took, and being bewildered by their dismissal of Helen Garner and Cate Kennedy while they lauded Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Carver – as though men writing about domesticity were groundbreaking, whereas those themes were banal coming from women writers.’

Much of the feedback has been utterances of relief, as woman around the country discover their struggles don’t belong to them alone. And in the end, Clarke wishes for a positive impact.

‘I hope the open dialogue and comradery between Australian women writers that we’ve seen in the last few years continues to grow. I hope readers will think about the kinds of comments women have been making when purchasing or reading a book, and be conscious of whether unintentional gender bias is influencing their buying, reading or borrowing habits.

‘I hope male readers will read more work by women. I hope male writers will realise and acknowledge their privilege and be more aware of their interactions with their female counterparts. I hope editors, publishers and booksellers come up with new and innovative ways to support both emerging and established Australian women writers.’