twilight might be over, but the plotlines continue to disturb

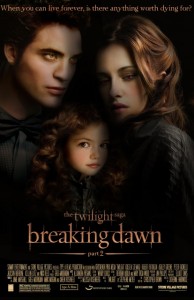

Thursday the 15th of November marked an important day for pop-culture enthusiasts the world over – it was the release date for the final Twilight film. Breaking Dawn: Part 2 hit our screens and signalled the end of a multi-million dollar franchise that spawned many a feminist critique, and many a fanfiction tribute.

Whether you loved or hated Twilight, you can’t deny the impact the series has had on young adult fiction more broadly. It’s hard to walk past a bookstore these days without being inundated with black-covered novels, with red text and words like ‘kill’, ‘lust’, ‘blood’, ‘hungry’ or just straight-up ‘vampire’ in the title. Whilst I continue to yearn for the good old days of Looking For Alibrandi and Tomorrow When The War Began, I did also read Twilight and I get where the appeal comes from.

Twilight is everything a (trashy) young adult novel aspires to be in a sense – entertaining, titillating, and engaging without being too serious. Ultimately a love story, the addition of supernatural themes gave the series just enough bite (pardon the pun) to set it apart from other trite romance novels, while still remaining relatively PG and inoffensive. I mean, these vampires don’t even drink human blood. They’re so harmless, they’re kind of boring.

Breaking Dawn was definitely the most boring part of the whole series. Two thirds of the novel is focussed on Bella being pregnant with a demon child and spouting a lot of thinly-veiled pro-life bullshit, and the rest is filled with her and Edward having a lot of vampire-sex and trying to protect their supernatural child from a potential threat that never truly eventuates.

This threat comes from the Volturi, vampire royalty who are in charge of keeping vampires hidden from the human world. Thinking that Bella and Edward’s child, Renesmee, might be a threat to their secret status, they travel to Forks to kill her and possibly the whole Cullen clan. The Cullens pool their resources and assemble a vampire army to oppose the Volturi with. The two groups meet on a snowy battle-field, poised to fight, but instead… they just talk about it. And then part peacefully.

I suppose I could look at this as a shining example of not resorting to violence to prove the legitimacy of your demon spawn, but really, I was just disappointed that the one time there was opportunity for real action in Twilight, Stefanie Meyer copped out.

I went to the film of Breaking Dawn Part 2 expecting it to be terrible, and for the most part, I was right. There was the usual awkward acting on the parts of both Kristen Stewart (Bella) and Robert Pattison (Edward), stupid plotlines and terrible musical score.

The whole thing was underdeveloped, trite and reasonably uninteresting. That said, the final ‘battle’ scene was well shot, had a twist that left most of the audience gasping, and lasted for just long enough. They also added enough additional scenes to the film to make it slightly more entertaining than the novel.

I wouldn’t really recommend anyone watch the movie unless you can score free tickets, but I did leave the cinema feeling unsettled by more than the dodgy choctop I ate and the terrible screenwriting. There are enough weird and unbelievable plotlines in Twilight to make me feel uncomfortable, but the one that I really can’t get my head around is that of Jacob and Renesmee.

For those who (fortunately) haven’t read the books or seen the movie, let me give you a quick rundown. Jacob is a teen werewolf who is originally in love with Bella, and who forms the third point in the love triangle that’s the central focal point for the first three books of the series. One of the bizarre aspects of ‘werewolf magic’ is that often werewolves ‘imprint’ on an individual, tying them to that person for life. ‘Imprinting’ is more than just love – it’s an incredibly close, unbreakable bond, and it flows both ways. The fact that the word ‘imprint’ itself has some nasty, power/control connotations that worry me aside, the creepiest thing about the whole concept is that there is no guarantee that the werewolf will imprint on someone who is age-appropriate.

In the case of Jacob, he imprints on a newborn baby, the half-human, half-vampire child of Bella and Edward, Renesmee. I know. Ewww. Supposedly, while Renesmee is a baby, his affection for her is in no way sexual, but it is accepted throughout the novel that the sexual attraction will grow with Renesmee’s own aging. So, even as the child Renesmee sees Jacob as a doting uncle, he’s aware that they will have much more than a simple uncle-niece bond in the near future. Again, eewww.

The fact that Jacob knows this and remains connected to Renesmee is weird and predatory – he insinuates himself into her childhood, and predestines her to be his life partner without her having any real choice in the matter. Renesmee will never have the chance to grow up, meet guys, and make a choice based on her experiences. It’s no better than an arranged marriage, in a sense.

Sure, Meyer implies that Renesmee also imprinted on Jacob, but frankly, that makes no sense and the concept is far more fraught when you consider the fact that she is a newborn baby when her and Jacob first meet. There is no agency on Renesmee’s part in any of this, and it’s far from acceptable in my eyes.

However, Twilight fans don’t seem that concerned, and I’m yet to see any real criticism of the plotline. I think that’s for two reasons. Firstly, it’s a novel, and the ‘it’s just fantasy’ line is one often taken with books like Twilight that have shaky moral foundations to begin with. And fair enough – it is just a novel, and I don’t think that readers are all just passive consumers who can’t critically engage with what they’re reading. I don’t actually think that this ‘imprinting’ plotline will have any connotations beyond the series itself.

That said, I think that Meyer uses a specific context to justify a lot of the creepy, controlling and often just inappropriate stuff that happens in the series, that I think connects to certain broader ideas of looks and purity. For a start, all of the ‘good’ people in the novels are both young and attractive (or at least look young and attractive). The fact that Edward is in fact over 100 years old and is in love with a 17-year-old at the beginning of the series is justified by the fact that he still looks 17. Ultimately, he has lived through an entire century, which no doubt has aged him somewhat mentally, but the disparity in his and Bella’s ages is never a real issue because it doesn’t look wrong, therefore it can’t feel wrong. It goes without saying that if Edward looked is 100+ age, the whole story would take on a far more sinister edge. Added to this are his superior looks more generally, which help cement him as a desirable boyfriend figure, despite his controlling, jealous behaviour a lot of the time.

Similarly, the fact that Jacob is young and hot exempts him from being labelled a pseudo-paedophile. Sure, he never does anything untoward with Renesmee as a child, but the whole relationship there is problematic and fraught with issues. Jacob’s age prevents him from being characterised as exerting any inappropriate influence or power over Renesmee – at 17, he is basically still a child himself, right? It’s an incredibly tenuous argument, that relies equally on the idea of Jacob being attractive to justify the bizarre nature of his attachment to the child.

If Jacob was the average teenager – pimply, pasty, maybe a bit scrawny, probably not entirely attractive, his attachment to Renesmee would be way more weird. Jacob’s superior good looks help construct him as a ‘good’ and ‘righteous’ character, and help the audience to disconnect from both the hideous age-gap and the creepy connotations of ‘imprinting’ generally.

This isn’t surprising. Looks are often used in literature and film to demarcate between the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ characters – rarely will you find a hero that is hideous, or a villain that is super sexy (although the latter is definitely more common than the former).

In Stefanie Meyer’s world, ‘attractive’ and ‘good’ are conflated regularly. Her characters are so two dimensional that if they are ‘good’, all of their actions are good. Jacob is a goodie, not a badie, so his attachment to a newborn baby, that is hinged on a future sexual relationship, is undoubtedly pure.

Conversely, the Volturi are ‘bad’ so their (reasonable, in many ways) fear of a potentially destructive child is both unreasonable, violent and corrupt by nature.

If only real life was this simplistic, eh?

What worries me isn’t the fictional town of Forks and the bizarre shit that goes on there, but what this says to readers and consumers about valuing physical appearance, and morality more broadly.

There is already a high premium placed on good looks in our culture – physical attractiveness will get you places that intelligence, charisma, and niceness just won’t. According to some studies, the better looking you are, the more likely you are to get a job, get a raise, or get job recommendations. Overweight people suffer the most, with a Yale University study suggesting that obese candidates are less likely to be hired, are characterised as ‘less conscientious’ and ‘sloppy’ and ‘lazy’ by both employers and health professionals.

There is no doubt that we moralise appearance – physical characteristics are implicitly linked with assumed personality traits. Think of hawk noses, bushy eyebrows, baldness, acne, the list goes on.

When fiction like Twilight reinforces these messed up ideals, it just continues to encourage people to value looks over skills, talent, intelligence or personality.

In the case of Jacob and Renesmee, it allows a cognitive disconnect to occur when reading about a situation that would be completely untenable if the parties involved where just slightly different in age and appearance.

Ultimately, I know that Twilight is just fantasy. I know that imprinting isn’t a real thing, and that to sell books and films, you have to allow for escapism and create characters that are drool-worthy enough to get your audience hooked.

But when a pseudo-paedophilia plotline can slip by with this little attention, I can’t help but feel somewhat disturbed.