demystifying the ‘female voter’

The ‘female voter’ is a vital component of the current US presidential campaign. Attempts by candidates Barack Obama and Mitt Romney to woo the vote of women have been under scrutiny in the media, and online commentary. Romney’s infamous ‘binder gaffe’ is an example of a more laughable attempt to garner support amongst women, but specific appeals to female voters are visible throughout both candidates’ campaigns.

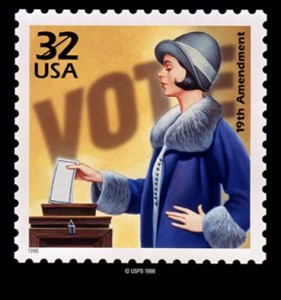

It seemed simplistic to me, as a feminist, that 50 percent of the population is lumped together and so targeted by politicians, both in the US and here in Australia. A recent article in the Washington Post listed the ‘Five Myths’ of the female voter, and the number one myth was that ‘women vote together’. This was my biggest concern with the ethos of targeting ‘female voters’, as my issues are vastly different to those of women from different areas, ages, and socioeconomic backgrounds to me. I began to question the origins of the concept of the ‘female voter’, and its enduring presence in contemporary politics, and set out to find more on this issue.

The US presidential race has garnered a lot of critical attention here in Australia. I spoke to one commentator, Dr Tim Verhoeven from Monash University, and learnt that perhaps I shouldn’t be so quick to jump on my high horse.

The Washington Post article highlighted the fact that white, married women from rural and suburban areas traditionally voted Republican, while the Democrats were favoured by urban, educated single women. So if women traditionally vote down party lines, how effective are attempts to appeal to a ‘female voter’? Does boasting of binders full of women (Romney) or telling a sad story about a little girl who lost her father in the 9/11 attack during a debate (Obama) sway a female voter, or are broader party policies what draw women in?

According to Verhoeven, a key reason for the focus on the ‘female voter’ isn’t as reductive as ‘get one, get them all’, but rather, in the States, women are more likely to vote than men. He claims that, ‘There are more women of voting age than men, more women are registered voters, and they go to the polls in higher numbers. In a system where getting people to the polls is often the difference between winning and losing, this makes women voters a particularly prized constituency’. Women are not targeted as a minority, but rather a voting majority. The history of a gender gap since the 1980 election has in fact seen a greater inclination for women to vote Democrat, and men to vote Republican. ‘In 2008, women favoured Obama by seven points’, and this makes securing the female vote crucial for the Republican party, particularly given the strong lead Obama held in the early polls (around 16%).

While there’s no doubt that the gender gap covers some big issues that sway voters, such as race, sexuality, and age, the fact that the vote of women can sway an election is pretty big, and knowing this makes the candidates’ play to women voters a little more understandable. With the understanding of the role of women in deciding elections in the US, what becomes critical for feminist observers is the way the two parties work to provide policies that support women across all elements of government policy. Verhoeven believes that the Democrats tend to do well with women because polls suggest women have expectations for the state in terms of welfare, gay marriage, and the role of the military more in line with the party’s policies. These policies obviously extend beyond reproductive rights and the role of women immediately associated with the term ‘female voter’.

What is interesting is the fact that both candidates have moved away from focusing on traditional ‘women’s issues’, to address how broader policies, such as the economy and foreign policy, impact on the lives of female voters. For example, in April, Obama said women weren’t a monolithic bloc, and has used the debates to draw women into discussions on topics like the economy and healthcare, while during the third debate, Romney tied foreign policy in the Middle East to the rights of freedom for women. These recent acts indicate that appeals to the ‘female vote’ are becoming more sophisticated in the age of political correctness. While it remains frustrating to perceive your gender as a target audience, the knowledge that politicians are growing aware of the critical role of women nationally and globally is heartening. While the term ‘female voter’ remains irksome, the relevance of the gender gap means it won’t be going away anytime soon, and suggests that women should embrace the power they collectively hold.

Tim Verhoeven is a lecturer at Monash University, specialising in modern American and European history, as well as issues in gender and sexuality.

Do you love independent media? Can’t get enough of intelligent, thoughtful feminist content? Want to see writers actually get PAID for their work? Please donate to Lip through Pozible today, and help keep the mag alive!