rethinking Hysteria and the regulation of female sexuality

Ah, the vibrator. A beacon of hope for singletons and a symbol of sexual liberation, this natty device has been making good vibrations since the 1870s. And what’s better than a machine which doles out orgasms? Okay, probably not much. But, if the response of film critics is anything to go by, the 2011 film, Hysteria comes pretty close.

Hysteria tells the story of the vibrator’s invention. From the 4th century AD, medical professionals believed many women were afflicted with ‘hysteria’, the ‘womb’s disease’. This disease was characterised by a wide range of symptoms, including loss of appetite, irritability, anxiety and ‘abdominal heaviness’. In her book, The Technology of Orgasm, historian Rachel Maines argues that these symptoms were in most cases indicators of sexual frustration.

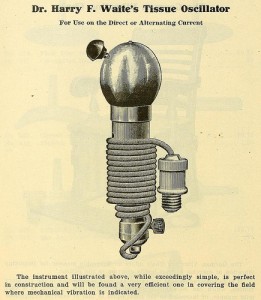

By the 19th century the most popular treatment for hysteria was for doctors to insert one finger in the patient’s vagina and perform a ‘pelvic massage’ to induce a ‘hysterical paroxysm’—orgasm. When doctors complained of exhaustion and physical hardship from treating patients this way, Dr. Mortimer Granville sought an easier method and created the vibrator. It was subsequently used by doctors and eventually became available on the public market.

Hysteria, directed by Tanya Westler, captures this story with quirk and spark, engaging audiences and portraying strong female characters to boot. Protagonist Charlotte Dalrymple denounces the sexist gender roles of her Victorian era, declaring that ‘mindless housework and doting on some halfwit…isn’t enough for (her), or for most women’. And the film’s overall positive and comparatively explicit depiction of women’s masturbation and orgasm promote female sexual fulfilment and liberation.

These points have earned Hysteria some acclaim. Curve magazine called it a hilarious ‘passion project’, while the review panel Let’s Talk Film says it’s perfect for those wanting ‘endless laughs sprinkled with a bit of feminist history’. Even Margaret and David described it as ‘fun’.

Yet, as The Guardian’s Alex Von Tunzelmann pointed out, ‘the reality probably wasn’t anywhere near as much fun as is depicted here’. Perhaps we need to consider the vibrator’s history a little more closely before declaring the film a feminist triumph.

Because framed in a different light, the treatment of hysteria by vaginal penetration could be described as rape.

In the introduction to Technology of Orgasm, Maines dismisses this interpretation, writing, ‘… orgasmic treatment could have done few patients any harm…It is certainly not necessary to perceive the recipients of orgasmic therapy as victims: some of them almost certainly must have known what was really going on.’

Hysteria paints a similar picture. Female patients are depicted as consenting through their smiles of guilty pleasure as they enter young Dr. Mortimer’s office. Dialogue hints at their full awareness of what the treatment entailed, and insatiable desire for more, as one patient requests extra sessions, suspiciously noting that her condition has become more severe, and another, still compromised by the pleasure of her recent orgasm, drunkenly chimes ‘Thank you, doctor.’

Though this may well have been the case for some women, it is hard to overlook the definition of rape, which ‘generally includes penetration of the genitalia by a penis, object, part of a body or mouth’ without consent.

So the greatest question here is: to what extent was consent granted for this invasive cure?

There is not sufficient evidence to dismiss the potential lack of consent to some of these treatments. In the first instance, many women were diagnosed with hysteria due to a wide array of symptoms it encompassed; hysteria was even diagnosed to those with ‘a tendency to cause trouble’. Some of these women would not have been in the mental state to consent; in 1873, the vibrator was first used to treat hysteria in women in an asylum in France.

Further, one could argue that the lack of information available to women about and the shaming of female sexuality at the time may have compromised their ability to consent. Charles Taylor even wrote in 1882 that women have ‘nothing of what is understood as sexual passion.’

Overall, these factors point to the need to reconsider the way popular media often frames the treatment of hysteria: as a site of hilarity and female pleasure. Rather, it could be viewed as a site of the control and regulation of women’s bodies and their sexuality, which in some instances may have amounted to rape.

Though Hysteria has some strong points, it might not be worth all the buzz.

You are, however, holding people that lived at least 100 years ago to modern standards of consent and social understanding of rape, which is truly unfair. Shaming the past is not the answer, nor is misconstruing it, as the film did. Learning is all that can be done, as there is no justice in judging.

If everyone was frightfully happy, cupcake, then why was there need for reform? I guess it was just those nasty feminists insisting you focus on your brain rather than pretty, pretty dresses and corsets. While we’re at it, let’s rethink slavery. Maybe that was okay as well. We wouldn’t want to be “judgey wudgey!”