sexism gets a rebrand: when did female objectification become progressive?

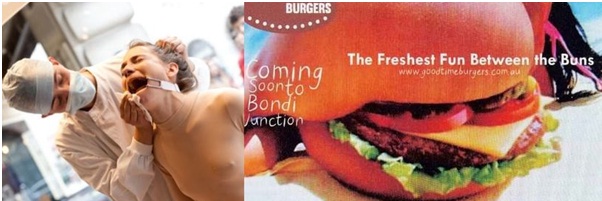

For those who missed it, obscure Bondi burger restaurant “Goodtime Burger” skyrocketed to infamy last month after publishing an ad featuring a woman’s outer labia as the meat in a hamburger bun. The caption read: ‘The freshest fun between the buns’, and sparked outrage from the public, with voices criticising the ad as “sexist,” “unappetising,” and having reduced a woman’s body “down to a burger bun.” The response to the ad was overwhelmingly negative, with food critics, advertising watchdogs and even staff members of the restaurant chain moving quickly to distance themselves from the image.

‘Guys I would like to make a public statement that we […] are so sorry about this picture. We were not in control of this posting. An exterior social media team was hired to manage this campaign and it was out of our hands,’ one employee tweeted.

The Australian Advertising Standards Bureau also banned the ad.

But is there a difference between an ad that exploits a woman’s body for capital gain, and one that does it in the name of a cause? Why is female degradation in advertising tolerated when it’s repackaged as a moral imperative? In the wake of the universally negative response to the Bondi restaurant’s ad, exploitative use of the female body continues to dominate elsewhere. Goodtime Burger’s distasteful ad has much in common with advertising utilised by groups that vehemently condemn exactly what Goodtime Burger is selling: namely, products that involve the slaughter of an animal. It remains unclear why animal rights groups are not bothered by the hypocrisy of using the same lowest-common-denominator tactics as their ideological opponents.

The release of the “Fun Between the Buns” ad and the subsequent outpouring of complaints about it coincides with the ongoing circulation on social media of images and videos of performance artist Jacqueline Traide’s 2012 participation in an animal rights protest at Britain’s Lush department store. In these images, Traide simulates the cruel treatment meted out to animals in laboratories. As per the requests made by a male actor dressed as a scientist, she is restrained wearing a nude bodysuit. She is hauled about on a leash, is force-fed until she gags and has irritants squirted into her eyes. A section of her head is shaved with clippers so that electrodes can be attached to her scalp. The week the protest was staged, The Guardian published a piece defending the protest, explicitly justifying the use of the female body to convey a message about animal cruelty. Entitled “Lush’s human performance art was about animal cruelty not titillation,” the piece explained:

‘We felt it was important, strong, well and thoroughly considered that the test subject was a woman. This is important within the context of Lush’s wider Fighting Animal Testing campaign, which challenges consumers of cosmetics (a female market) to feel, to think and to demand that the cosmetics industry is animal-cruelty free. It is also important in the context of Jacqui’s performance practice: a public art intervention about the nature of power and abuse. It would have been disingenuous at best to pretend that a male subject could represent such systemic abuse.’

Depressingly, the shock-tactic campaign was touted as a piece of performance art, which enjoyed an “overwhelmingly positive” response. However, the parallels between Lush’s protest and Goodtime Burger’s “Fun between the buns” ad are ominous and obvious when positioned side-by-side.

Lush’s protest would appear, at a first glance, to differentiate itself from the usual cheap and exploitative advertisements featuring the female body favoured by both Goodtime Burger and notable animal rights organisations. Lip Magazine published an article about these last year. Indeed, Lush’s Fighting Animal Testing campaign appeals to rather a different primal urge in the viewer: in the place of arousal, viewers are positioned to experience repulsion and horror at Traide’s endurance of routine animal testing procedures.

Nevertheless, the premeditated selection of a woman as the “test subject” reveals an eerily similar line of reasoning to those who thought using a woman’s genitalia as the meat in a hamburger bun was a good way to sell burgers. In other words, both advertisements seek to manipulate viewers through the positioning of women as passive, marketable objects. The lame justification that it is ‘disingenuous at best to pretend that a male subject could represent such systemic abuse,’ in Lush’s Fighting Animal Testing Campaign reinforces the unfounded assumption that women are naturally predisposed to experience disempowerment at the hands of men. The perpetuation of the dehumanisation of women in displays that are thought to be “powerful” and “morally upstanding” highlights the fact that media spin can make people blind to the sexism inherent in advertising. An artificial divide now exists whereby certain incarnations of violence against women are considered “acceptable.” This occurs even when female objectification is as blatantly offensive as a woman being singled out in order to be presented as an animal to be experimented upon. It’s no different to presenting a woman’s genitalia as hamburger meat to be consumed.

Further, both ad campaigns defy logic in that they disempower women through forced identification with the female being objectified. However, Lush’s protest is supposedly intended to encourage women to feel as if they are empowered enough to end the cruel practice of having cosmetics tested on animals. The Guardian article highlights the fact that Lush’s cosmetics boycott targets a female market. This is because women are the primary consumers of cosmetic products. To those who believe this is reasonable, I pose the following questions: How is a woman supposed to feel empowered if she is being singled out because of her gender to identify with a woman simulating pain on the end of a leash? Should she feel similarly empowered to buy burgers when she sees her genitalia simulating hamburger meat? Paradoxically, advertising across the board positions women as objects to be bought, and empowered market subjects simultaneously. These labels force women to be complicit in their own degradation. Subsequently, the targeting of women in the ad through shock tactics suggests that those behind the protest have zero faith in the intelligence of the female consumer. Why were images of female exploitation chosen in lieu of an awareness campaign based on publicising the alternatives to animal testing?

Before we pat ourselves on the back about the successful message conveyed about rejecting sexism that was spurned by Goodtime Burger’s “Fun Between the Buns” ad, sexism needs also to be addressed when it masquerades as “progressive.” Unfortunately, in a society that mistakenly identifies as “post-feminist,” images of female degradation continue to be disseminated in the public sphere in ways that do not encourage people to think critically about the discrimination behind them. Though some are easily identified and labelled “overtly sexist,” others that reappropriate the abjection of women and justify it under the vague and flimsy pretext of “humanitarian causes” are tolerated, and even applauded. In reality, these are a part of the problem. From a feminist standpoint, there is no difference between an ad that objectifies a woman’s body for capital gain and one that does it in the name of a cause. Realistically, a post-feminist society cannot be realised when the objectification of a woman’s body is still considered a reasonable platform for communication.