the feminist debate

Both a problem and a strength of feminism is that the label is an umbrella term, representing a multiplicity of (sometimes contradictory) views. Calling yourself a “feminist” means that you believe in the advancement of the role of women in society. What this necessarily entails could be anything.

One branch of radical feminism believes that women are not equal to men, but actually superior. Women who subscribe to this belief feel that we should live in a society without men, harvesting the sperm of the best specimens in order to continue the human race.

On the other extreme, there also exists a Sarah Palin-esque branch of feminism. People who believe in this think that women should have equal rights and equal pay as men, but do not believe in affirmative action. They figure that modern Western societies are liberal enough to allow women the choice to do what they want (within legal boundaries) and therefore feel that we live in a “post-feminist” environment.

Most feminists sit somewhere between these two ends of the continuum. They don’t want to kill men, and in fact they’re likely to note how gender roles can restrict men as well as women to the detriment of everybody. Equally, most feminists would also believe that there is still much work to be done in achieving equality and that the phrase “post-feminism” is naïve. Of course, the fact that extraordinarily different views of what the goals of feminism may entail exist, means that within feminist circles there is debate and contestation, even for people who don’t identify themselves as having an extreme view.

One issue that we still debate today arose after Roe vs. Wade, the landmark 1973 US case which legalised abortion – something that feminists generally could celebrate. Now that women had various means to control their biology – first through the pill and if that didn’t work, now also through abortion – sex no longer had the dramatic reproductive repercussions it once did. What were we to do with this new sexual freedom?

In comes the feminist debate on the moral status of the sex industry – of pornography and of prostitutes. On one side, you have feminists like Robin Morgan who says that ‘pornography is the theory, rape is the practice’ and strongly believes that this industry exploits and objectifies women as objects designed to suit the sexual desires of men. On the other side, there were feminists arguing the very opposite, that women have the right to express their sexuality; they have control over what they choose to do and all the better if they can make some cash out of it, particularly since traditionally women had been coerced into being sexual for their husbands for free.

One of the uncanniest things about this debate is that it aligned women with unlikely groups. For the side that felt that the sex industry was exploitative and didn’t like it, suddenly they were agreeing with the Puritanical right-wing of politics who felt that sex had no place in public culture. Meanwhile, feminists who were pro-sex industry were aligned with people like Hugh Hefner who worked very hard to legalise abortion and was at this stage building a magazine empire focused on men, their lifestyle and their sexual enjoyment. While both sides aimed for the empowerment of women, they were seen as being in agreement with people who are not all that interested in that goal. This makes debates in feminism even more difficult to handle.

Feminist debates exist for many other issues pertaining to women and their welfare. Should women choose to get married? Is it wrong for women to wear religious clothing, such as the burqa? Are shows like Two and a Half Men damaging for women? Should Julian Assange be trialled for rape? Feminists can reasonably answer these questions in different ways, including ‘I don’t know’.

But what implications do debates in feminism have for feminism more broadly? When a group of men and women have the same goal of equality, which is not a straightforward achievement and in fact quite a difficult task (in itself a premise that not all people who call themselves feminists agree with), shouldn’t we take some kind of united stance? Something that allows people to know exactly what it is that women need in order to be socially equal?

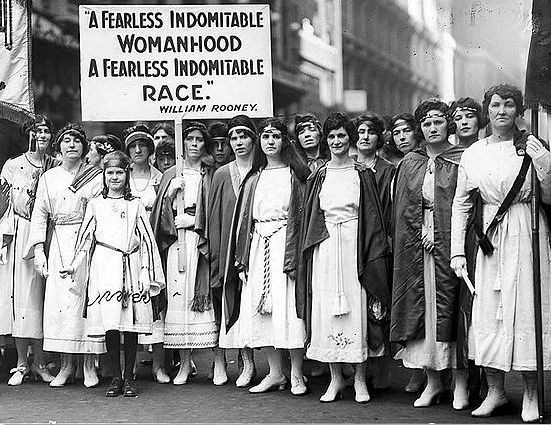

This question of unity in feminism arises from the split between the different waves of feminism. The first wave was really just about allowing women to vote in democratic elections and being allowed to own land, extremely important and tangible outcomes which were obviously achieved throughout many parts of the world. Second wave feminism came along in the 1960s and can be summarised with the mantra ‘the personal is political’. They were interested in freeing the domestic lives of women, in acknowledging that entering a relationship with a man and doing domestic activities in the home is not a life path that reflects the abilities or interests of women generally. They were also concerned with the pay gap between the genders, and why it is that in the workforce women generally have lower responsibilities and rankings. Third wave feminism, the wave that we are arguably in now (though there are debates surrounding even this), is different again – it’s all about giving women independent choice, allowing them to be unconstrained by expectations. A woman is allowed to do what she wants – she can marry or not marry, she can work whatever job she sees fit, she can stay at home if she wants and if finances allow, she should have as many children as she wants – and nobody should judge her for it. Success of this wave is measured through equality, presumably, for instance, as many women would like to be political leaders as men, and thus men and women should be equally represented in Parliament, as in places such as Norway (where women make up 39 per cent of political representatives) and Sweden (where women hold 52 per cent of ministerial positions).

Even though we are in the time of the third wave, many feminists would not necessarily align themselves with the views of the third wave. Such feminists might remind us that choice is complicated, that people aren’t just a product of choice, there are also certain expectations placed on women, particularly in relation to domestic duties and child rearing that makes it quite difficult (though not impossible) for women to become, say, a CEO. Other feminists might even point out that looking at how many women presidents and CEOs there are might be a really bad way of looking at how much choice ordinary women actually have in their daily lives.

In these times, where debates within feminism tend to be associated with asking ‘what outcome would give women the ability to choose?’, inadvertently the debates become an issue of ‘what is choice?’ and ‘what needs to happen in order to give people choice?’

Take the debate about women wearing the burqa in France. Many people argue that the burqa is oppressive and by allowing it, it restricts the choice of women as they are forced to wear it by the patriarchal forces of religion and the traditional Islamic family. Other people disagree completely, feeling that women are able to choose what they will wear, and that choice is between the individual woman and God. This is rough terrain because there are issues of religious brainwashing, family pressure, and the ability of women to decide for themselves what they believe. There are equally also issues in trying to understand how women come to the choice of wearing certain clothes generally. For instance, is a bikini, a garment that is purposefully scanty and revealing, empowering or oppressive? Do they really choose to wear a bikini or are they indoctrinated by the patriarchal forces of the fashion industry and consumer culture to believe it to be appropriate wear?

Here, we are actually getting into questions of what it is to be human. Are we mindless sponges soaking up all that we read, see on TV, hear from our families and are taught in school, or do these things not matter at all? If the answer is something in the middle, then the debate becomes a matter of to what extent are we or are we not manufactured by the situation we are born into? These kinds of questions are difficult to get a handle of; we may never find a convincing answer.

Answers to these questions are not easy and while a united front probably would help achieve the aims of feminism, it is equally important to make sure that the goals of feminism actually would bring about the advancement of women. Getting a united front might be effective, but deciding not to debate would be dangerous, even if it were possible. In addition, even if feminism is multi-faceted and lacking in unity, it is still necessary to remind ourselves that if another feminist has the goal of making the situation for women better than they need to be respected as an ally in a suitably complicated fight.

This article first appeared in Lip Magazine Issue 21. To purchase a copy of the current issue, click here.