hip hop: shake that arse for me

from issue 13: by Chloe Angyal

Picture it: two men are out on a Saturday night. Leaning against the bar, one of them turns to the woman next to him and says, ‘I hope you don’t get mad at me, but I told my friend you were a freak. He says he wants a slut, I hope you don’t mind; I told him how you like it from behind’.

Some women, myself included, would slap the man in question. Someone with a little more self-control might ignore him and walk away. Once done with the slapping, however, I would pause to think about what exactly he had said to me and, more importantly, how on earth he came to think that it was an acceptable thing to say.

The charming come-on in the above paragraph is actually paraphrased from lyrics uttered by rapper Nate Dogg in his recent collaboration with Eminem on the track ‘Shake That’, which is a narrative of the two men’s adventures on their night out at a strip club. Immediately after Nate Dogg’s line comes Eminem’s echo, also directed at the woman (again, put yourself in her shoes), ‘I hope you don’t get mad at me, but I heard that you were a freak. Tonight I want a slut, I hope you don’t mind, I heard that you like it from behind’. For the record—if someone approached me like that, he’d be crawling out of that club on his hands and knees.

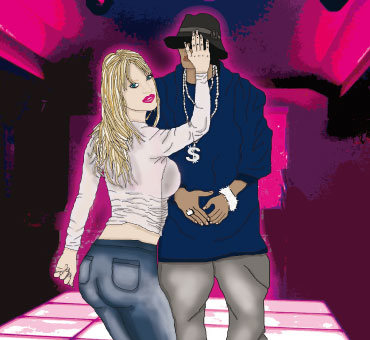

The hip hop movement, mostly in the form of music, has gained momentum in Australia in the last five years. Every year another few artists appear in the charts and for every single released, a video clip is made and played on network and cable television. The general point of these video clips is to construct an image for the hip hop artist—in the case of the male artist, he’s rich, famous and attractive (or in the case of less than physically perfect specimens, he’s attractive because he’s rich and famous), and he spends his life singing, driving his ‘pimped up ride’ and fighting off women with a stick (a stick that we can only presume is covered in bling).

The most commonly used video clip formula is the wall-to-wall women formula, where the man is in a club that appears to have no male patrons except for him. A good example is Nelly’s ‘Hot in Herre’ video clip: flattering lighting, industrial quantities of body oil and dozens of sweaty women who, not wearing much to begin with, obediently respond to the instructions in the lyrics, ‘It’s getting hot in here, so take off all your clothes’. Eventually it gets so hot that the emergency sprinklers come on, making whatever clothing remains cling to the young, lithe bodies of the suggestively dancing women.

OutKast’s ‘I Like the Way You Move’ video portrays women as safari animals—lions, giraffes and antelope—grazing the plains in bathing suits and high heels, while hunters, played by the band’s two male singers, watch them through binoculars. This kind of symbolistic objectification of women has a lot to answer for.

In a recent forum, lip asked young women how images in hip hop make them feel about themselves, including whether it affects their ideas of what’s considered sexy. Several responded that the images don’t affect their own ideas, but felt that they do mould men’s ideas of sexiness, which in turn affects how they are viewed by those men. Therefore, the images that appear so often in videos can indirectly affect women who don’t even watch them. Thinking about this, it doesn’t seem fair that young women who choose not to consume the hip hop culture can’t avoid the expectations it sets up.

Natieka, an eighteen-year-old girl from Washington DC, wrote, ‘videos and lyrics don’t really affect what I think is sexy, but they do blur the lines for girls as to what is truly expected by men sexually’. And she makes an excellent point. If young women take what they see in video clips as a truthful indicator of what men expect from them, then our generation is in serious trouble indeed. These women are no role models: scantily clad, oiled, made up and draping themselves over male rappers who refer to them only as ‘bitches’ or ‘hos’.

As the charming and subtle Eminem and Nate Dogg demonstrated earlier, hip hop lyrics paint ugly pictures of male – female relations. Usually, the acts of sex described in these songs are entirely one-sided affairs, with the man’s pleasure being the top, and sometimes only, priority. The woman’s sexuality or sexual needs are barely considered, except for the disclosure that ‘she likes it from behind’, which earns her the label of ‘slut’. It should be noted, as per usual, when judging sexual habits of men and women, that his plan to bed every woman in the club does not make Eminem a ‘slut’, no matter how many times he does it from behind. Even more concerning is the implication that enjoying sex seems enough to make a woman a slut. I know plenty of women who enjoy sex, who crave it and think about it as much as their male peers, but that’s not slutty—it’s human and normal and totally acceptable when guys do it. A hip hop synonym for ‘slut’ is ‘freak’, and it’s very rare to find a man being referred to as a freak.

The lyrics to Petey Pablo’s ‘Freak-a-Leek’ are revolting, but telling. The rapper describes his ideal woman as—and I’m paraphrasing, because a direct quotation is unprintable—someone who ‘wants to try new sexual positions, isn’t scared of a big penis and loves to receive oral sex from another woman, because I’m not drunk enough to do it myself’. No, I’m not joking. This man wants an adventurous (and presumably flexible) woman who isn’t afraid of a (presumably his) large penis, and who doesn’t mind if he, Mr Pablo, has absolutely no interest in her sexual pleasure. Damn, don’t you just want to jump in line to be that girl?

The young women who responded to the online forum gave intelligent, insightful answers, which should give us hope—clearly not every girl out there wants to grind on a bling-clad rapper and head back to his hotel room for a groupie-esque night of catering to his (and only his) every sexual desire. I’m incredibly proud of the many lip readers who recognise that, as women, we can choose how men see us; we don’t have to accept the images hip hop holds up as the ideal.

I’m not proud of the women artists in hip hop who succumb to the pressure of the industry and become loud, influential enforcers of that ideal. Destiny’s Child’s last release as a group was ‘Cater 2 U’, and for the three girls who once topped the charts with ‘Independent Women’, what a turn around it was. ‘When you come home late tap me on the shoulder I’ll roll over/…I’m here to serve you’. Um, what? Apparently the men of hip hop aren’t the only ones guilty of portraying women as sexual toys or servants. It’s even more offensive when women have internalised the image enough to want to sell it to other women; a sick form of self-sabotage.

I’ll be the first to admit that a great beat is irresistible. And I’m not suggesting that we must boycott a beat because we don’t like the lyrics laid down over the top. What I am suggesting is that young women learn to watch and listen critically. Do we really want to be giving our money to a section of the music industry that promotes such appalling treatment of women? And do we really want to emulate the images we see in hip hop, sending the message to young men that it’s okay for them to treat us the way rappers treat their hos? We are not hos, we are not freaks, we are women. And we are fabulous.