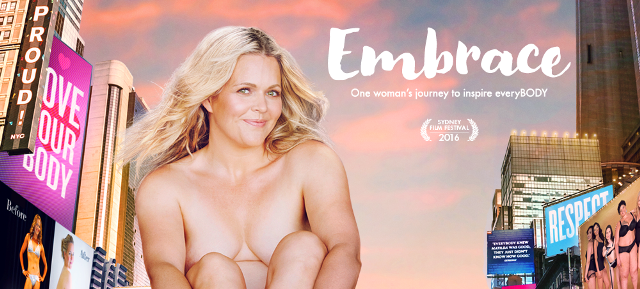

film review: embrace

Body image sort of feels like one of those topics that we, as a society, should have conquered, put aside, and moved onto bigger things. It feels like a topic that we have collectively heard so much about: incessantly, I am bombarded with inspirational quotes on social media telling me to ‘love myself’. We have all heard for what feels like aeons now how women on covers of magazines are photoshopped and don’t really look like ‘that’ in real life, and how the women that media and advertising fetishise are not necessarily representative of all bodies. And yet, body loathing remains a significant issue for many women.

In many ways, because it is often the victim of over-simplification, body image as a discussion topic has become somewhat boring to me. Yes, I know that positive body image is important. But while I think the vague, general importance of this message has not been missed by many, it has been internalised or embraced by few. My tiredness with the simplification in positive body image campaigns made me a little resigned to believing that Taryn Brumfitt’s Embrace documentary would be another film in a long line of attempts to solve the nuanced complexities of body image in far too superficial ways. But I was very pleasantly surprised to find that the film adopted a more considered, multifaceted approach to the topic.

Taryn Brumfitt is the mind behind Embrace. The documentary was born after her own unfortunate experience with online body shaming. The movement began when Brumfitt successfully subverted the tired trope of before and after pictures, by sharing a “before” photo of herself during a body building competition and an “after” shot of herself soon following childbirth. The comparison was intended as less of a comparison and more of a statement upon the fact that a woman can love her body even if it does not fit nicely within the very narrow parameters of socially-dictated “beauty”. Although many online received the photos positively, the post also attracted trolls, as women’s bodies unfortunately tend to. Nonetheless, her post went viral and attracted mainstream media attention. Brumfitt then began The Body Image Movement and garnered the impetus to create Embrace.

Debuting earlier this year, Embrace comprehensively canvasses body positivity. Interviewing a range of body image advocates and researchers, Embrace attacks unrealistic standards pursued by cosmetic industries and media, the sexualisation and objectification of women and girls in today’s society, and the pervasive scrutiny of a woman’s appearance to the ignorance of her substance as a person.Brumfitt travels around the world to interview different women for her documentary, and simultaneously manages to survey a wide subsection of women in numerous cities. In doing so, she is able to attain a general barometer of these women and their own “real” body perceptions – the general consensus being varying degrees of dissatisfaction.

Brumfitt takes stock of how the biggest feeder of body image problems is the constant expectation placed on women to change how they look, and the associated notion that once they make these changes they will be happier with themselves. Brumfitt focuses on the way that cosmetic, beauty and other appearance-centric industries create the problem with women’s bodies while simultaneously providing illusory solutions on how to “fix” these bodies. Ultimately, this creates harmful thought patterns that subtly reinforce the belief in women and girls that there is something inherently wrong with them.

Embrace engages with insights into the modelling, film and media industries, cosmetic surgery practices, body obsessions – from thigh gaps to labiaplasty – and how negative self-perception can contribute to harmful dieting patterns, often manifesting in eating disorders. Brumfitt herself reflects on the inordinate amount of time and effort it took to look the way that she did in that “before” picture; that is, to fall within the narrow social ideal. She calls attention to the fact that people can be healthy and active no matter how they look. In considering such perspectives, the documentary challenges societal beliefs of the need to change women’s appearances, and the default unhappiness that many women have with their bodies.

There are some moments in the film that are a bit too saccharine and fluffy. At times it drifts too far towards seemingly suggesting that positive self-image is easily attainable, not the hard-earned effort that it is for many. But at least the importance of the documentary’s message is never confused or estimated. Embrace constantly works to centre itself on the broader consideration of why women are positioned to hate the way they look and how these negative perspectives can be shifted.

But overall the most important message of Embrace is probably that appearance shouldn’t matter at all. Brumfitt regrets that she has spent too much of her life plagued by body and appearance-related anxieties, and that she hopes that, through her positive role-modelling, her daughter doesn’t experience the same regret. Although it is perfectly understandable that body image anxieties will continue to re-emerge at different stages in most people’s lives, it does not have to be an all-consuming insecurity.

For me, the take away message from the documentary was the emphasis on the fact that even positive-reinforcement for women and girls is, in a way, negative reinforcement. And by the end of Embrace, the documentary itself is calling for us to move on from these insecurities and focus on more pressing issues in our own lives. Bodies should be seen as a vehicle for action, to utilise in order to experience life and move from place to place, both literally and figuratively. Rather than centring our attention on the external, let’s shift our focus to the type of people we and other women and girls are, and on our skills, talents, characters and minds.