the lip crew on influential feminist books

Can you recall the first feminist book you ever read that opened your eyes and had you nodding your head along with every sentence, every idea, every truth?

*

“‘Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine,’ growls Godmother of Punk, the girl who just wanted to look like Keith Richards, Patti Smith. With her dishevelled hair, lanky legs and penchant for men’s white shirts, Smith’s attitude, music and attire could easily be interpreted as a two fingered repost to the patriarchy and the stifling conditions it enforced upon women during the 1960s and ‘70s. Yet in her own words, Smith did not purposefully strive to dismantle sexism, saying of Feminism that ‘the issue of gender was never my biggest concern; my biggest concern was doing good work. When the feminist movement really got going, I wasn’t an active part of it because I was more concerned with my own mental pursuits.’ Despite her comments, it cannot be denied that throughout her life and career, Smith has constantly rebuffed the traditional conventions placed before her, and smashed through any barriers that hampered the journey of her poetry and her music.

Her award winning autobiography, Just Kids, recounts her move from Jersey to New York, her meeting and eventual relationship with the cult favourite photographer, Robert Mapplethorpe, and the perpetual journey she tramps from poverty, to living in the infamous Chelsea Hotel to the recording of her album, Horses. While the text was not written as a distinctly feminist piece, Smith’s ideologies and morals within the book and throughout her creative life have never ceased to inspire me; to encourage me to reject the pre-ordained system laid out before me. She says that it’s OK to want to dress like a boy and have ragged, loose hair. She encourages diversity in one’s own creative process. She taught me that collaboration is good, and to not focus on money, but instead on building a good name. And if that determination and refusal to back away from one’s destiny is not a feminist motif, then I don’t know what is.

The book is a favourite of mine, and the paperback copy I own has become weathered and worn from repeated readings. Each time I fall into a fallow period in my life, where my pens and paper sit idle on the desk and my mind empties of all inspiration and energy, I pick up my copy of Smith’s musings, and I allow her words – her journey – to wash over me and revive me once more.” – Made Stuchberry, Writer

“Greer’s wit-infused feminist call to arms, The Female Eunuch, never had much of an impact on my feminism. Or me. I found it poking out of the bookshelf in our suburban family home when I was sixteen years old. I was immediately struck by the scandalous, transfixing cover of the beaten-up paperback. It was a woman’s naked body, hanging in the air like a damp tea towel. It appeared to be disemboweled, with shoulder straps instead of arms and handles instead of hips. Naturally intrigued, I read on. This was my first encounter with the idea of ‘feminism’, when I was decades away both from the era during which it was written and from my own assumption of the associated pressures, stereotypes and expectations on adult women that its author was so aggressively indicting. Add to that the energetic feminist’s often hyperbolic, incoherent and dated-sounding prose style, and the whole thing felt more like a chore than a rallying cry, an academic experiment more than an awakening.

That is not to say that The Female Eunuch was not and is not an influential book, even for me. Encountering it years later while in university – my radical mind being awakened by the subversive atmosphere that can only ever inhabit a privileged educational institute – I came to understand if not fully subscribe to the revolutionary ideas that it imparts.

It has now become fashionable to affect a faint embarrassment about Greer, like a batty great aunt who sits in the corner making disquieting remarks about the Germans. Her intellectual promiscuity has undoubtedly taken her down some controversial routes – according to Varsity, she once suggested that trans women are not women because they do not know what it is like ‘to have a big, hairy, smelly vagina’ – and there are several subjects on which she is wildly out of step with the modern feminist consensus. But the point of Greer is not to be cautiously correct or to make you feel better. It is to be thought provoking, and occasionally enraging. She is a stimulant, not a painkiller. Greer was the woman who opened my eyes to feminism, and from the 1970s to now, I’m certainly not her only willing victim.” – Eden Faithfull, Writer

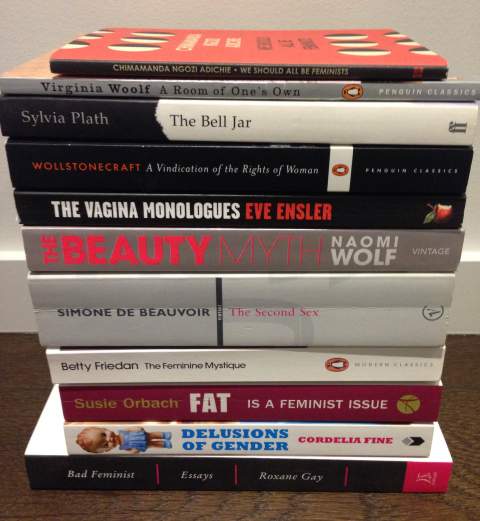

“I have a shaman friend who believes that when your soul recognises a truth, a shiver runs down your spine. I’m usually a critical thinker but this rings true when I think of the influential feminist texts I have read. From reading about cunt hatred in Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch and from realising I myself am a brain in a jar (like Caitlin Moran espoused in How to Be a Woman), I got shivers. Musings that for women’s writing and sexuality to be valorised, we must not imitate that of men’s gave me the tingles – they were enshrined in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and Ariel Levy’s Female Chauvinist Pigs, respectively. Then there’s Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists; a mere morsel of a monograph, its succinct, elegant articulation of the universal need for feminism details Adichie’s experiences of inequality in her native Nigeria.

It’s wonderful that feminist literature has amplified voices from academia and beyond to shout one truth: women are not treated the same as men – not now, in the past, in developing nations and those which are wealthy. Feminism plays out more and more online and in other media. It’s wonderful; it promotes our cause with succinct sass and great reach, but we should always refer to our books to ensure our arguments entail deeper analysis and critique of the patriarchy and other structures inhibiting women’s rights. All women’s voices are needed in feminism, and we must ensure they are committed to paper.” – Sarah Iuliano, Features Editor

“I first read Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl when I was fourteen years old, which is around the same age Anne was when she wrote it. Not only is it a candid account of life under an oppressive war, it’s also just as much an explicit coming-of-age manifesto of a typical young woman trying to figure out her feelings and aspirations.

Initially Anne wrote the diary solely for her own eyes, but after hearing an announcement on the radio in 1944 that the exiled Dutch government was looking for accounts of Dutch people under German occupation, Anne begun editing her diary with hopes to publish it as a book after the war was over. Of course she never had the chance to, but her father – Anne’s only remaining family member – was given Anne’s diaries after the war, and as was her wish, published them as a novel in 1947. When the novel was first released, it was uncommon for young adult books to talk explicitly about sexuality and female desire. Yet Anne’s diary was a candid and certainly accurate example of the changes all girls go through when they reach teenage-hood.

In typical teen fashion, she writes about clashing with her parents and sister Margot, her secret longing for fellow annexe dweller Peter and daydreams about becoming an author. I found myself relating very much to Anne as I had similar thoughts and feelings that I could not quite understand that I too wrote down in a treasured diary. Instead of dismissing the ideas, feelings and dreams of young women like so many other novels do, The Diary of a Young Girl allows girls to explicitly address these things and encourages them to not feel ashamed about the changes they’re going through in the early teenage years.” – Jade Bate, Writer

“I have never queried that I was a feminist or baulked at the label because the term had very early-on been made simple and palatable by a family full of loud, uncomplicated feminists. Until quite recently, my understanding of feminism had no concept of how race, culture, class, education, sexuality or ability could intersect with gender. My notion of Feminist Dilemmas oscillated between hair removal and the forgoing of maiden names. The notion of internal disagreement within feminism was utterly foreign to me. The idea that feminism itself could be discriminatory or oppressive was unable to fit into my neat and tidy conception of the sisterhood. Lorde’s essay The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House (from Sister Outsider) was one of the things that showed me how basic, and often exclusionary and problematic, my own feminism was. The essay was part of my tentative grasping at the notion that oppression does not come as one-size-fits-all; that as a white, straight and able-bodied woman my experience of sexism is a specific and limited one.

Re-reading the essay to write this piece I was struck by the references Lorde makes to the importance of community among women. My most instructive and moving experiences of feminism have come from collectives and communities of women. This was initially something I queried when I recognised that my actions in women’s spaces have tended to buy into traditional notions of feminine behaviour – we sit and chat and whinge and cry and nurture one another. Lorde’s essay helped me see this not as a capitulation to a reductive stereotype but a necessary and empowering reaction.

This essay showed me that feminism is a messy, rapacious, contradictory beast; that the absence of tidy cohesion and united experiences is a thing to relish and explore, not ignore or deny.” – Arabella Close, Writer

“I picked up Braided Lives by Marge Piercy by chance. It was closing day at my favourite bookstore and I happened to catch the cover of the novel (all white except for a photograph of a bespectacled girl in a plain sweater standing in front of a bookshelf) while waiting in line to buy something else. Braided Lives was and remains unlike any coming of age story I’ve ever read. At its core, it’s about the horror of going to college in an era without legalised abortions. But what I remember most about Piercy’s novel is the strength of friendship in the face of classism, sexism, broken hearts, independence and assault even when life takes you in different directions. Piercy treats Jill and Donna, best friends and cousins, with respect and honesty even as they make drastically different life choices. It’s a beautiful and difficult read but worth every minute.” – Shannon Clarke, Writer

“The most influential feminist book that I’ve read has to be Unspeakable Things by Laurie Penny. I had seen it in a post from Amanda Palmer, who is one of the most inspiring women in my life, and decided to pick it up based on her recommendation.

It’s raw and gritty and holds no punches. The most significant thing for me about this book was that it was the first time I’d read anything that discusses the connection between toxic gender roles and mental illness.

As someone who has spent a considerable number of years struggling with various mental health issues, from depression through to disordered eating and self harm, it was revelatory to me that gender roles and stereotypes could have a huge impact on a person’s mental health, almost especially that of women. In a culture that feeds of women’s self hatred, it isn’t any wonder that so many of us end up learning more about self destruction than how to love ourselves.

Also think about the conflicting messages women receive on a daily basis. You should be skinny, but not too skinny. Be polite and don’t make a fuss, but don’t be a pushover. If you don’t have sex you’re a prude, but if you have too much you’re a slut. Be smart, but not so smart that men feel threatened. And on, and on.The rest of the book delves into the issues of slut shaming, online harassment, the commercialisation of love, and rape culture. It speaks to the rage in the pit of my stomach at the perpetual sexism and violence that women experience. It helped inspire me to get involved in social justice and activism, reminding me to never stay silent when there is injustice.” – Ruth Scott, Writer

Pingback: news round-up 9.8.15 | lip magazine