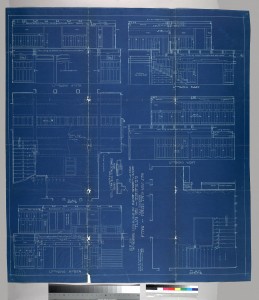

blueprints: the future of women in architecture

On Wednesday, a panel of four women in architecture came together to discuss the plausible future of their professions, which featured Sydney architects Stephanie Smith, Rachel Neeson, Camilla Block and Imogen Howe. All graduates of the University of Sydney, the speakers collectively had extensive experience working for large Australian and international architects, infrastructure companies and running their own practices over the last three decades.

The panel speculated on different roles women might play moving towards a more equitable and robust profession. If the survival of the profession long-term depends on diversity, how might this be reflected in architecture’s demographics, ways of working, and modes of practice? How should a practice be redesigned to support diversity? How does gender equity expand the definition of architectural practice and engagement, and what does this offer the discipline and community? These are just a few of the questions that the panel tackled.

And tackled they certainly were. The speakers were extraordinarily passionate, and concurrently warm and witty; unsurprising for a group of gifted women. Despite their humour and affability, the experiences they recounted were far from being a joke. In the realm of architecture, it’s a well-known fact that women still cluster in the junior ranks of the profession, despite having comprised nearly half of all architecture graduates for more than two decades. Beyond this, the panel’s facilitator and co-founder of Parlour, Dr Naomi Stead, stated at the opening of the forum: ‘The architecture industry finds itself beleaguered in the current market – disempowered, marginalised, and subject to pressures that make it difficult for architects to stay afloat.’

Throughout the panel’s discussion, members of the audience chimed in with incisive questions ranging from women’s abilities in the business side of architecture, to the inevitable question of balancing professional responsibilities with childbearing, each of which received an empowering answer. Both Ms Neelson and Ms Block responded similarly, stating that they were the number crunchers in their businesses and their male partners were the ‘dreamers’ – the idea of being a women getting in the way of balancing equations filled them with warranted shock. The discussion even managed to maintain its decorum after being interrupted; not once, but twice, by a more elderly member of the audience who had quite obviously indulged in one too many of the complimentary glasses of Chardonnay: ‘The way to leave your mark as a woman in architecture is to marry a plumber, or an electrician, or a construction worker. They know where to dig the holes. They know where the shit goes.’

Samuel Johnson, an English writer of the Sixteenth Century, once said: ‘Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.’ It appears this primitive view is still repeated throughout the male-dominated architectural sphere. Not all hope is lost, however, as demonstrated by a small sample of hardworking women, who deny the title of “superwoman” while running their businesses and dropping their children off to school. Their work is their passion, but it does not consume their lives or immediately negate other responsibilities. It was a true honour and pleasure to have listened to these women’s experiences, and opportunities such as these serve to remind us all that women do not need to approval or praise of a patriarchal industry. Empowerment comes from within, and with hard work and conviction, we can do more than just stand on our hind legs; we can kick ass.