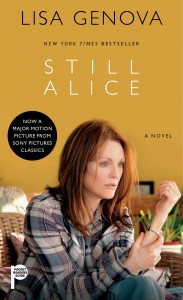

lip lit: still alice

‘I’m losing my yesterdays…so what I have to say today is timely.’ – Alice Howland

It is a brave thing to write a book about Alzheimer’s disease. The topic is heartbreaking enough in itself, as the disease has no known cure. It is also a dangerous representation to get wrong, as with all representations of mental illness. But it can be achingly beautiful if successful.

Lisa Genova’s Still Alice is all three: brave, heartbreaking, and achingly beautiful.

For the novel’s protagonist to not only be an Alzheimer’s patient, but also the book’s sole narrative voice, is a fascinating exploration of both the ‘unreliable narrator’ device and the intimacy with which mental illness can be presented on the page.

‘Still Alice’ is a New York Times bestseller and has recently been made into a film starring Julianne Moore. I’m yet to see this movie, so this review shall be based entirely on my experience of the novel, but let it be known that I will be buying my ticket the second I have the chance.

Our protagonist Alice Howland is a Professor of Psychology at Stamford, as well as a wife to John and a mother of three grown-up children. At 50, she is at the peak of her professional, personal and physical life when one day she forgets a single word during a lecture she has given multiple times. After a few months of downplaying the increasing gaps in her memory, Alice reluctantly consults a doctor and is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s.

This turning point sets the course of the novel. Alice struggles to maintain the speed and responsibilities of her old life, and ultimately, inevitably, to let that life go.

This journey would be emotional enough without the first-person, present tense narration. But the author chose this perspective for a reason.

Genova said of her narrative strategy:

‘I thought it was the most powerful choice. In telling the story through Alice’s lens, I sit the reader right up against her Alzheimer’s. It should feel uncomfortably close at times. You should feel her confusions and frustrations and terror right along with her.’

And I did. The slow mental deterioration of Alice’s mind instils a growing panic in the reader, especially when eventually, with a rush of pity and dread, you can feel her mistakes coming.

Alice’s doctor says at one point that Alice ‘may not be the most reliable source of what’s been going on.’ A simple statement to give an Alzheimer’s patient, but in terms of the novel it forces us to consider everything she has described for us so far.

Are there small mistakes in her expositional paragraphs? Are there large ones? How many degrees have we been deviated from the truth?

Little by little, we lose our faith in Alice. Eventually we feel that we know more about her life than she does, and the fact that only a hundred or so pages can give us such a sense of authority over Alice is sadder still.

Additionally, the fact that Alice was a highly successful and respected female Professor, in a field dominated by men, brings a fresh sting of melancholy. Alice says many times that she is proud of her academic achievements, at one point going on to wonder if her husband John would have achieved as much, had he also gone on maternity leave three times.

All her accolades have been fought for in the face of the patriarchy.

And when, inevitably, her Alzheimer’s leaves her incapable of maintaining this professional standing, it feels as if the significance of all these victories are fading along with her memory.

It is horrifying to watch a strong, intelligent female character like Alice being stripped back by mental illness.

Despite its overtone of heartbreak, however, Still Alice is anything but bleak. It is lovely to see how Alice’s relationships change with the people around her: how she slowly exchanges work for family on her list of priorities. This is clearest in the case of Lydia, her youngest daughter, who at the beginning of the book is frowned upon by her parents for choosing to pursue acting over a university education. Just about my most favourite part of the book was watching Alice become accepting of Lydia’s choices, and learning to love her for the passion of which she once disapproved.

Alice’s husband John was also an incredibly real and complex character; it was painful to watch him initially refuse to believe that Alice was sick. His love for Alice surfaces through his fear of watching her fade away. This is presented with such intimacy and precision that even though he is physically distant throughout much of the book, I never doubted him.

Of course, ultimately, Still Alice cannot be expected to have a happy ending in the traditional sense of the word. But I do believe it ends on a hopeful note.

As Alice says, her yesterdays are fading, so today is all she has and that must be enough. To live for (and love) the contents of single moments; to focus on what we can do now rather than what we have done.

If nothing else, read it for that.

For your chance to win a copy of Still Alice, email [email protected] with your name and address. Competition closes February 28.

Im Nursing….Alzheimers is a tragic death of a personality before the body also succumbs….but some tragedies also have their sweet lovely moments….. I’m wanting to see the film AND read the books….. clutching tissues for both I imagine…..

Pingback: film review: still alice | lip magazine

Pingback: Review: Still Alice (20 Feb 2015) – J. M. Miller