2013 and gender inequality in film

While list articles are one of the best things about wrapping up the end of the year, Lip prefers to look back at 2013 in a typically feminist way: representational analysis.

Over the last few weeks, our writers have looked at how women have been portrayed in the media, and then the Australian media’s attitude towards females has also been scrutinised last week.

But how do we see women in film? And what does that mean for us?

There were a heap of movies you would have watched in the last year without considering what gender the protagonists were. Stop and have a think: when was the last time you watched a film that had a female protagonist, screenwriter or director? When was the last time the leading lady was allowed to keep her clothes on? There has been a lot of recent discussion about the representation of women in film.

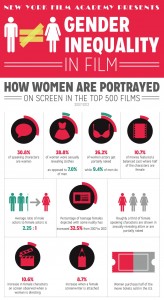

The New York Film Academy put it all into a handy dandy infographic for your viewing pleasure (click on the image for a better view).

When you first look at the statistics surrounding the disproportionate representation of women on screen, they are depressing to say the least. A study conducted by the Southern University of California looked at the top 100 highest grossing popular films of 2009. The results were staggering:

- Less than 17% of the films analysed were regarded as ‘gender balanced’.

- Women accounted for just 32.8% of speaking roles.

- When women were present, they were more likely to be sexualised—meaning they were wearing ‘sexy’ or revealing clothing, were ‘attractive’, or were partially or completely naked.

These findings are only further supported by studies conducted at the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media. Founded by actress Geena Davis, the institute advocates for and works hard to instill more gender balance in the entertainment industry. Their study on roles in children’s television programs showed that yet again, men were more likely to be a lead character. Women had fewer lines, were less visible, had specific ‘gender’ roles, and were not as ‘responsible’ as the male characters. They were also more likely to have an ‘unrealistic body ideal’ with an ‘uncharacteristically small waist’.

In summary, women were outnumbered by men 2:1. These findings, though disturbing on any level, are particularly worrying when you consider that children are the ones consuming these gender stereotypes—thus reinforcing and perpetuating inequality.

Along with gender roles, the depiction of female sexuality is another problem inherent in films. Very recently, actress Evan Rachel Wood exploded over Twitter in response to a sex scene being cut from her upcoming film, Charlie Countryman. It appears the only reason the sex scene was cut by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), was because it featured a man giving Wood’s character oral sex. If this ‘offensive’ scene hadn’t been cut, the film would have received the highest possible rating in the US (NC-17), meaning it was less likely to be shown at theatres and make money.

‘Someone felt that seeing a man give a woman oral sex made people ‘uncomfortable’ but the scenes in which people are murdered by having their heads blown off remained intact and unaltered,’ said Wood. Unfortunately, this example yet again shows a blatant censoring of female sexuality.

Wood noted that by considering scenes of sexual violence and male sexual pleasure to be ‘acceptable’ on screen, the MPAA was creating discrimination against female sexuality, which could only culminate in further gender inequality. ‘Accept that women are sexual beings. Accept that some men like pleasuring women,’ she said.

Despite all the doom and gloom, there’s certainly an array of women trying to break free of gender stereotypes on screen, or work behind the scenes to ensure more equality during production. Brit Marling, an actress and screenwriter, is one inspiring lady. She has written and acted in three of her films: sci-fi drama Another Earth (2011), psychological thriller/drama Sound of My Voice (2011) and recent thriller The East (2013). Marling concentrates on writing strong, multi-faceted female protagonists. She has therefore created characters for herself that reflect a diverse range of roles for women: a young woman who serves time for manslaughter; an undercover agent who infiltrates an eco-terrorist group; and a mysterious cult leader.

In an interview, Marling says one of the reasons she started writing her own films was partly due to the severely limited roles for women. “If I did get an audition or a part it was for…some awful, terrible horror movie where the girl is just… [the] victim and being like dragged around,” she says.

There’s also everyone’s favourite, Lena Dunham, who is one of the most influential women of 2013—so influential that she is the only celebrity I can safely follow on Instagram without feeling like a total creep, or at worst, a celebrity worshipper. If you haven’t seen Girls, and you’re feeling a bit disillusioned with the world due to other shows about girls in the city (Gossip Girl, for instance) then this show is a must-see.

As many critics have similarly observed, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire was also a very refreshing exception to the male-dominated arena of popular blockbuster films. Jennifer Lawrence’s Katniss Everdeen is undoubtedly one of the best mainstream female characters I’ve seen in a long time.

The question remains: how can help eradicate gender disparity on screen? From an audience’s point of view, one answer is the Bechdel test, which many would already know originated from Alison Bechdel’s 1985 comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. To pass the test, the film must contain two women having a conversation about something other than men. It sounds easy, but it is deceptively hard to pass. Once you start looking into it, you can be sure to find that many of your favourite films wouldn’t pass.

It was recently scrutinised when four Swedish cinemas committed to using the test. Although this move was contentious, it is at least breaking the conventions of film watching, forcing us to think about the consequences of what we watch. When you consider the cold, hard facts, small actions such as introducing the Bechdel test may seem trivial.

It is clear that there is still a long way to go in disintegrating the essentially patriarchal structuring of the film business.

Pingback: In Brief: Study finds films that pass Bechdel Test make more money | lip magazine

Pingback: Sexism in Hollywood Cinema | markleeyr3